On 17 April 1917 the second battle of Gaza commenced with the ‘diggers’ surprising the Turks by approaching from a very difficult direction over steep dunes. They managed to push back the Turks and secure Shellal and the water supply. The decamping Turks abandoned their machine gun post and it was in one of those trenches that signalman Corporal Ernest Lovell-Shore from the 5th Light Horse Regiment (LHR) noticed an intricate pattern in the wall of the dugout. The Signalman had just uncovered one of the best examples of Byzantine art from the period 561-562 AD. The Turks, in digging their fortifications, had exposed and at the same time partially destroyed what was to become known as the Shellal Mosaic.

Colonel Lachlan Wilson also of the 5th LHR placed a cordon to protect this newly discovered antiquity and ordered Sapper Francis Leddingham McFarlane, a signalman from the New Zealand Wireless Troop, to colour sketch the mosaic to ensure that a faithful record of its construction was made.

The order was made to excavate the find. The Shellal Mosaic’s main character is the Most Reverend William Maitland Woods. He was an Oxford-educated man who had already seen action at Gallipoli and subsequently transferred to the 7th LHR as Senior Chaplain to the Australian Forces in Egypt as one of Lieutenant General (Sir) Henry Chauvel’s staff. Rev Woods had a keen interest in archaeology and, with the high command approval, set about planning the extraction. The mosaic lay exposed for weeks before its removal.

It was not until early June a team of 32 men laboured in searing heat for 12 days to painstakingly transfer these marble pieces, the average size of which was 10 x 5 mm). Each piece had been carefully placed into a 5 cm bed of plaster of Paris covered with tibbin (a finely cut straw used for camel feed) to keep the treasure secure. Finally, 63 wooden crates were sent to Cairo while the War Trophies Committee, based in London, decided their fate.

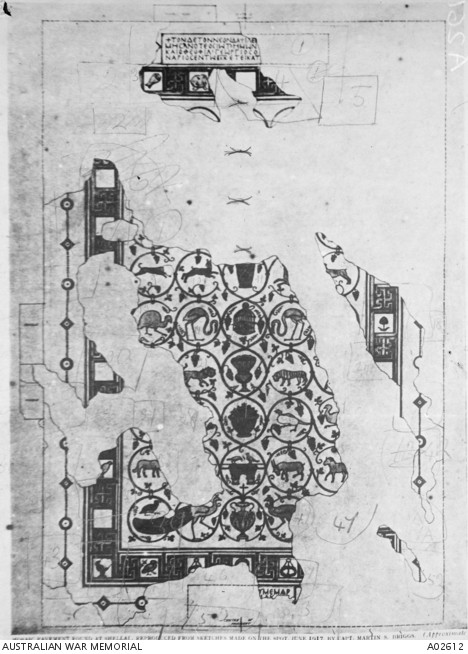

During the excavation, Reg Walters visited the site several times, as referenced in his letter. As an artist, he was intrigued by the mosaic’s artistry and had spoke about it with Rev Woods whilst he sketched. Many ‘visitors’ came to the site as word of its discovery spread, the many brightly coloured stones and pattern segments being a tempting war souvenir! Several drawings were done of the mosaic between the finding and extraction. Comparing the first, by McFarlane in April, to ones done later, such as Captain Martin S Brigg on 3 June, provide significant evidence of ‘trophy hunting’. In the earlier drawings, the peacocks were complete and there were nine lines of decipherable inscription below the animals. In later drawings of the mosaic however, the stones which made up the figures, a large area at the bottom right and part of the inscription beneath were gone.

The mosaic itself was dated 561-562 AD by reference to the Greek inscription on the eastern section of the floor. What makes it such a significant archaeological find? Firstly, it was a Christian chapel (church) from the Byzantine period when Hellenic pagan culture began to meld with Christianity. Secondly, Marble was an expensive commodity and not commonly used, other than by the very wealthy. Thirdly, the use of exotic animals from different lands, such as lions, tigers, flamingos and peacocks all paying homage to a central chalice, could point to other pagan races and lands embracing Christianity. Lastly, Rev Woods discovered a chamber under the mosaic containing human bones lying with the feet to the east and arms closed on the chest. The bones and inscriptions had Rev Woods very excited, more than the pattern of the mosaic, as a rough translation of the inscription let him to think they were the bones of St George.

In April, the original floor measured 15 x 8 m. What was recovered measured 8.7 x 5.4 m with a single field within a border. The border is represented by black and white interlinked swastikas, with the field divided into 45 circular medallions in nine rows of five. These are formed by a vine trellis flowing out from a two-handed amphora to form the medallions, flanked by two peacocks at the bottom.

The bones that Rev Woods had discovered were not those of St George, as he had hoped. More probable is that the bones were of a local bishop of the time known as George. Fearing the bones would be sent to England forever, Rev Woods gave a ‘parcel’ to his friend, Rev Herbert J Rose, for safe keeping. That parcel contained the bones of George, which found their way to Rose’s parish of St Anne’s at Strathfield in Sydney, where they are interned in the floor in front of the church’s communion table. Rev Woods’ fears were justified as, during the repatriation of the remaining bones from Cairo to London, George’s skull disappeared - never to be seen again.

Rev Woods, concerned that the treasure might not reach Australia, gathered up several baskets of tesserae (the individual pieces from which a mosaic is made) from the site and had an artisan fashion an exact replica of the inscription headstone, measuring 1 x 0.5 m. He gave the completed replica to a friend, Colonel John Arnott who, after the war, returned to his family property at Coolah, NSW, and embedded the replica into his garden steps. The property, and the step, is still within the family today.

Rev Woods, determined the mosaic would not fall totally into the hands of the British, then sought out Canon Garland, another close friend from St John’s Anglican Cathedral in Brisbane, and entrusted him with the section of the mosaic bearing the Greek inscription. This panel can be found today embedded in the floor in front of the altar of St John’s, Brisbane.

It was not until 26 December 1918 that the crates were loaded onto the MV Wiltshire for shipment to Australia. There was no permanent home for the mosaic until construction of the National War Memorial was completed and officially opened, appropriately on Remembrance Day, 11 November 1941. The Shellal Mosaic, arguably Australia’s oldest non-indigenous or religious relic, is housed fittingly in this memorial.

Several questions remain:

Did the Australian War Memorial receive all the crates?

Where is the rest of ‘George’?

How many descendants of WWI veterans have pieces of the Shellal Mosaic, and do not know the significance of these brightly coloured stones?

Patric O’Callaghan